Graduate Capstone

- Joy

- Aug 22, 2024

- 15 min read

Updated: Aug 24, 2025

Reconstructing the Threads of History: A 3D Exploration Through Medieval Fashion, Gender, and Craft

Introduction

Through the digital adaptation of a Burgundian noblewoman’s garment, this capstone addresses the underrepresentation of women’s roles in history by using late medieval fashion as a lens to explore status, identity, and agency. The garment is set in an interactive 3D educational experience that uses setting and implied narrative to highlight women’s participation in nontraditional roles, such as political and military involvement. By integrating craft, technology, and feminist inquiry, the project offers a fresh perspective on women’s power and presence in late medieval Europe. It also serves as a model for how digital tools and game design can be used to produce and present historically appropriate reconstructions of cultural heritage, and thereby make valuable contributions to the study of history more broadly.

Final Result

Unreal Engine 5 Executable

You can download the game here.

Physical and Digital Reconstruction

Research Paper

My research paper can be found here.

Defense Presentation

My capstone defense presentation can be found here.

Table of Contents

Methodology

As a graduate student in Visualization with a focus on game development, I approached this project using a workflow rooted in game industry practices. This methodology, however, is not commonly applied to cultural heritage projects. As a result, my project had an unusual emphasis on certain phases, particularly the research and concepting phases. Overall, this project draws from interdisciplinary practices in historical research, game development, and visualization. With each having its unique advantages and techniques, a combination of their influences has contributed to design decisions in different ways.

Among these disciplines, historical research introduced the concept of historical appropriateness. This involves defining and understanding the difference between historical authenticity, historical accuracy, and the use of the term historically appropriate. According to Burgess and Jones, lecturers on narrative brands like video games, historical authenticity is when media mimics history but isn't factually accurate or true. Conversely, historical accuracy uses extensive research to create convincing depictions without true concerns if its process was accurately applied. (Burgess and Jones, 817-820) However, the scholars in “Refashioning the Renaissance” focused on a single inventory note when approaching the historical reconstruction of a garment. Drawing on researched materials, techniques, and construction methods, they used available resources to create a garment they determined to be historically appropriate. In doing so, they took certain liberties in the reconstruction, guided by their interpretation of historical evidence. In other word, research informs design decisions, making it historically appropriate. The historical value of this project stems from my commitment to appropriateness mainly in garment construction. Due to the given constraints of time and manpower, as well as the goal of creating an engaging player experience, the project results in historically authentic setting.

Nevertheless, the depiction of women's roles, attire, and garment construction remains firmly grounded in academic research and historical sources. This resulted in the adoption and application of historical appropriateness to this project.

While historical research shaped the foundation, industry practices from game development offered a structured production workflow. In game development, the process typically begins with an idea, followed by research into the visual and technical elements needed to bring that idea to life. From there, developers produce code and create both 3D and 2D assets, then package everything together, playtest for issues, and launch the final product. Due to the crossover nature of this project, my workflow deviated by placing greater emphasis on early-stage idea development and historical research than a typical production pipeline. Thus, during the ideation and conceptualization phase, I used photobashing techniques in combination with historical references. This included both 2D and 3D concept iterations of garment designs and environmental settings. Due to an emphasis on historical appropriateness, one garment style was focused on based on visual and literary references.

During the development phase, efficiency was achieved through kitbashing environments using premade assets combined with custom models to recreate a historically appropriate setting. This workflow integrated easily with Unreal Engine and allowed me to focus more on the garment and research. For example, I used Unreal Engine 5’s Metahumans, which provided lifelike character models with built-in support for animation. Animation, although not implemented, can be a part of future development. Traditional character modeling, by contrast, is time-consuming and requires multiple specialized skills, including creating the 3D model, simulating hair, texturing the model’s appearance, and structuring joints for desired movement or posing.

The garment was developed in Marvelous Designer, utilizing historically accurate patterns derived from thorough media analysis and primary sources to ensure fidelity to period construction. The final deliverable was programmed in Unreal Engine 5, a free industry-standard game engine with real-time rendering capabilities, support for interactive 3D environments, and advanced physics simulations. This platform allows viewers to engage in an immersive 3D environment through an easily shared executable.

Below is a Miro board with my collection of notes, references, ideations and process.

Technical Workflow

Garment Construction

My interest in the connection between fashion and craft influenced this project. In aiming to develop a digital reconstruction, I researched different aspects of garments that I might recreate, from textile weave to garment patterns.

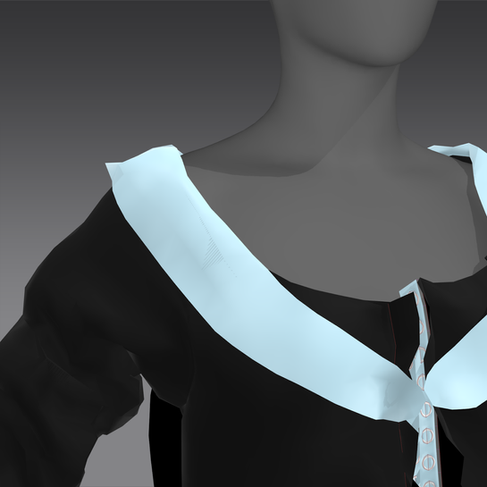

After examining the weave structures and their digital simulation, the next step was to analyze patterns and translate them into the 3D space. Through my research, I found patterns that best suited the style in “The Medieval Tailor’s Assistant” by Sarah Thursfield. I referenced several patterns, including the fitted gown pattern pictured below. It consists of a front and back piece, collar, sleeve, and cuffs

I also found the patterns for the hennin, frontlet, cap, and veil.

Using several historical pattern books as references, I compiled information on the garment’s construction and began the digital modeling process.

Marvelous Designer operates similarly to other 3D modeling programs, featuring a workspace where the garment is visualized in a 3D environment. What sets it apart is a second window for 2D garment pattern drafting, using tools reminiscent of Adobe Illustrator.

These 2D shapes correspond to fabric panels, which are simulated and draped over a 3D avatar. To fully take advantage of Marvelous Designer, a foundational understanding of sewing and garment construction is essential, as most of the tools use the same language and functions.

The avatar I chose to use is the “medium average” body type that Metahuman offers, which best fits those of the noblewomen I observed in my references. Body customization in Metahuman is limited in comparison with their facial editing capabilities. There are only three body types: underweight, medium, and overweight. The only variations are height (short, average, and tall), for a total of nine avatar choices.

You can import the images of your patterns into the 2D window, set the scale to your preferred unit of measurement, trace, and sew corresponding pieces together. Based on my research, I chose to take liberties with the published pattern by adding a hidden lace-up piece in the front panel, which was mentioned in my research. This was not indicated in the pattern itself, so its construction was my development. This decision, despite its historical backing, presented collision issues when draping the fabric. I then later learned that Marvelous Designer has no function to thread ribbon through the eyelets. Instead, the effect must be simulated by attaching a fabric piece to a hidden circular piece to create the illusion of lacing.

Although Marvelous Designer can simulate various types of fabrics and allows adjustments to their warp and weft, the user must still manually drape the fabric onto the avatar, simulate, adjust, and repeat. This iterative process introduces multiple variables, which can result in points of deviation within the simulation that do not visually align with historical references. For example, when working on the collar, I was met with a persistent issue in how it draped around the neck. Despite following the pattern’s recommendations for sewing, shape, and placement, the distortion continued to appear.

This led me to pursue a physical reconstruction through the use of CLO3D, a fashion industry software focused on manufacturing. This was to allow for a mediation between the digital and physical construction, so I could better understand what was going wrong in the digital garment. CLO3D’s relation to Marvelous Designer allowed the import of my file to be relatively easy. However, this method led to unexpected results. I learned about some gaps in digital garment construction logic. For example, seam allowances are pieces of extra fabric added beyond the original pattern to enable sewing without altering the intended measurements. I had to add this manually, then exported the file as a DXF, or drawing exchange format, in other words, vector-based data of the pattern. Through troubleshooting and the help of Michael Gayk, my committee member and expert in digital fabrication, I later exported the file as a PDF into Adobe Illustrator. I cleaned it up to be used in the software called Sure Cuts A Lot for use in a plotter, and the patterns were then plotted onto paper.

Additionally, in order to understand the digital version, I had to create a dress form that had the same measurements as the digital Metahuman. With the help and advice of the College of Performing, Visualization, and Fine Arts’ costume shop manager, D’Mya Tabron, I learned that the dress form required measurements that have not existed on dress forms since the Victorian era. So, since what they had available could not be used, I had to then use an available dress form, cut it, and pad it out to size.

The collar’s shape remained consistent across both the physical and digital versions. This alignment validated aspects of the original pattern and suggested that, despite some simulation limitations, Marvelous Designer was able to accurately reflect the intended pattern. In contrast, the front and back pattern pieces did not appear to align in length, revealing a discrepancy that became more noticeable in physical construction, but not visible in the digital version.

With the digital garment complete, I was able to export the 3D model and import it into Unreal Engine. In the end, the garment construction proved to be an exploration in both the technical and physical aspects that challenged notions of historical appropriateness.

Unreal Engine 5 Blueprints

For this project I developed different Unreal blueprints for the functionality I needed within in the executable.

Main Menu and Main Level

These are standard level blueprints for the main menu button functionality, and the camera being set to the user in the main level, as well as applying UI elements.

Object Highlight

I also created a blueprint that when hovered over by the player, objects were lit by a spotlight to indicate its interaction ability.

Blurb Popups

When the object is clicked by the player a pop up with information appears and can be closed once read.

UI/UX Elements

With my interest in illustration, I applied my skills in creating the UI/UX elements with the use of Adobe Illustrator, Photoshop, and After Effects.

Conclusion

Despite being largely confined to roles centered on marriage, childbearing, and childrearing, medieval women often held responsibilities that extended beyond these expectations. While women are rarely depicted performing these extended responsibilities, historical evidence shows that a woman’s social status could afford her forms of empowerment. This project challenges our limited portrayals of medieval women by presenting a noblewoman, dressed in historically appropriate fashion, acting as a war strategist.

Through the digital exploration of fashion, gender, and craft, my work reveals how gendered roles intersect with status, identity, and agency. A noblewoman’s marital status shaped her identity, which in turn influenced the roles and power available to her. Yet her gender still dictated what she was allowed to wear, and the garments themselves were products of cultural norms. As women were often responsible for managing the household, they also played key roles in textile production, creating garments that reflected regional trends and the moral expectations placed on them, especially by men.

In highlighting this complexity, my project makes visible the ways fashion functioned not just as adornment, but as a coded language of power, virtue, and agency in medieval womanhood.

As a result, this exploration of garment construction generated a representation of a woman in historically appropriate attire, acting in a position of power within an immersive and believable environment. The combination of visualization techniques and contextual information provided to the player through pop-ups, which can be read in the Appendix, connects ideas related to women's status, identity, and agency. This combination allows history to be more accessible, engaging, and immersive. My game allows the relationship between women’s roles and the garments they wore to be rediscovered not just for women gamers but for all audiences.

Analysis and Outcomes

In working on a digital reconstruction, I encountered various limitations and issues, such as hidden bias in digital tools, where the body types of female avatars provided by Metahuman do not necessarily reflect real human bodies. This reveals an underlying bias surrounding the ideal female body in an inherently male-dominated digital space. Upon closer inspection, the language used to name the body types (underweight, medium, and overweight) and the real-life measurements to which these types correspond reveals unrealistic body standards. The "medium" digital body alone was so unusually proportioned that this resulted in the need to build a custom physical dress form for the real-life reconstruction of the garment. This later presented issues with draping fabric on the body, both digitally and physically. The physical version's bust was too wide for the physical pattern, and the waist was too small. The digital version posed issues with the draping at the collar and the bust, making it difficult to adjust. The integration of customization into the Metahuman bodies would resolve the misinterpretation of women’s bodies and perhaps allow for scholarly work to have more access to believable, ready-to-use 3D human assets.

Marvelous Design was not without its flaws either. When developing a lace-up front, I quickly learned that a true lace-up was not possible. Instead, they must be created through hiding geometry and attaching it to the eyelets, only creating the illusion of the lace-up. This is an issue when attempting to produce a historically accurate garment. The development of a tool that automatically creates lace-up sections with adjustable drawstrings could be a helpful addition not only for fashion designers but also for game developers.

During the physical reconstruction, I also found that modern fabric bolts are too narrow for many of these historical patterns. For example, the back panel could not be cut as a single piece. This suggests that historical textiles may have been woven on looms wider than those used today, which adds another layer of difficulty when sourcing materials for accurate physical reproductions. Beyond this, working on a physical reconstruction alongside a digital version helped me recognize how my digital and hands-on skills could complement each other in creating a functional, real-world product. With prior experience in garment construction and sewing, I found Marvelous Designer intuitive, as it mirrors much of the same language and logic used in physical garment construction. In the Visualization program at Texas A&M, the curriculum is structured in a linear way. It begins with physical sketching, sculpture, and design, which are later replaced by digital tools. If these approaches were taught side by side, the practical application of our work would not only feel more tangible but would also open pathways into interdisciplinary fields.

Even the use of existing assets for the environment brings on challenges of appropriateness. Thus, connecting history and the final product involved research not only of the garment but also of the setting and war strategy. For example, some environment kits did not have certain key aspects of the architecture for the period. With more time or investment in the team that develops models, environments could be much more accurate. There are many cultural history projects that work on digital twins, which focus on translating real architecture and objects into the digital space through custom models and even scans. My project points toward ways that the process of creating digital twins could be made more efficient.

Future Direction

In future iterations of this project, I aim to create a fully realized interactive game designed to encourage learning and exploration. It would show different periods, roles, and women, and potentially portray real historical figures. For example, there is a Metahuman plugin that allows you to integrate any custom mesh. I could model a historical figure and seamlessly import it into the game. The environments could also be more historically appropriate, based on real locations connected to the lives of real women in history. Another possibility is the inclusion of physical garments that audiences could wear and further immerse themselves.

Since this project was created in Unreal Engine and it has compatibility for virtual production, it could be developed into an interactive museum installation. This might follow a model similar to the experience offered by the Abraham Lincoln Museum. There, curators utilize a physically realized space and combine human interaction with simulated figures using Pepper’s Ghost to engage audiences.

The game could also be made more accessible and educationally powerful through a web browser version and the integration of a publicly available library of historical patterns. This could be used in education settings that touch topics like history, the medieval, fashion and gender studies. The addition of a feature that displays the garment patterns and the simulation of the textile weaves through the use of my weave tool, for players, would introduce visual dynamics that grab and keep the audience's attention.

Weave Tool

Studying thread and weave structures required more hands-on research. The Brazos Spinners and Weavers Guild introduced me to various textile weaves, the tools they used to create them, and the language to convey their construction. With this information, I began developing a tool that simulates various types of weaves using Houdini. This is done through two line nodes for the x and y axis, set the points to primitive type, and copied to make a square grid. Both x and y connect to a group node, where a base group, or a selected group of points, is put into a list. The next node is an attribute wrangle coded to separate the x and y positions of each point, and raise only the y if selected.

int cols = 10; // Grid Columns + 1

i@row = int(@ptnum / cols);

i@col = int(@ptnum % cols);

// Raise selected points only

if (@group_raise_y) {

@P.y += 0.025;

}

The addition of an add node copies these points to be used with another wrangle node, which uses code to identify rows and columns of points. This helps with the direction of the thread that goes from edge to edge.

int cols = 10; // number of points per row

int rows = 10;

for (int r = 0; r < rows; r++) {

int pt_ids[] = {};

for (int c = 0; c < cols; c++) {

int pt = r * cols + c;

append(pt_ids, pt);

}

int prim = addprim(0, "polyline");

foreach (int pt; pt_ids) {

addvertex(0, prim, pt);

}

}

This is then used with a resample SOP to resample the curves into a series of polyline segments or lines connecting the points, where a polywire node makes this line into geometry. Finally, using a merge mode, the x and y are both visible.

Currently, this tool is capable of taking a user's input of chosen points to create a swatch of weave.

Once fully developed, this tool will enable visual designers to select a weave type that is procedurally and visually simulated, serving as an effective teaching aid, visual, and game development tool.

Houdini, considered to be an industry leader in 3D modeling, animation, and visual effects, “... is used by numerous leading digital content creation facilities including: Blizzard Entertainment, Blue Sky Studios, Double Negative, DreamWorks Animation, Electronic Arts, Framestore, Guerrilla Games, Pixar Animation Studios, and Sony Pictures Imageworks.” (Side Effects Software 2013, 1) Houdini’s versatility and broad range of applications made it a software I wished to utilize and integrate into my work. Due to time constraints, I did not apply it to the final project.

Appendix

Informational pop-ups that educate the player when clicking around in the environment.

Item Clicked: | Info Blurb: | Additional Blurbs: | |

Food on the table. | Contrary to modern media portrayals, war strategy in medieval times wasn't always planned over grand maps with figurines. More often, it took place around banquet tables in great halls, where strategy was discussed amid food, politics, and power. These gatherings were frequently hosted by members of noble lineages, and during times of war or upheaval. | ||

The great hall. | This wasn’t a neutral room. Often used for multiple purposes: weaving, eating, and even wartime strategy sessions. | ||

Noble woman | In times of war, noblewomen weren’t just spectators. When husbands were absent or fallen, they took their seats at strategy tables, voicing political insight and familial stakes. | ||

Garment | |||

Garment - Status | Her garment signals status. How? Color and Construction. The deep shade of Burgundian Black was notoriously difficult to produce, making it an expensive dye reserved for the elite. Associated with both secular and religious authority, black became a fashionable choice among noblewomen, appearing in nearly 36 percent of women’s gowns between 1485 and 1557. Status was also conveyed through excess. While most people wove only what they could wear, the nobility had the means to purchase large quantities of fabric, allowing for voluminous gowns that swept the ground. | ||

Garment - Identity | Garments in the Middle Ages were heavily gendered. Literature like The Book of the Three Virtues justified that women practice prudence and sobriety, so they had to dress the part. Fully covered and stripped of intricacy, their clothing ensured they didn’t commit the sin of pride. After all, fashion, and the vanity it signaled, could be dangerous. Some even feared it might trigger another flood, like the one in the Old Testament. | ||

Garment - Agency | Her status as a noble afforded roles not often given to women of the lower class. In life, if her husband permitted, or in death, if he was tragically lost, noblewomen were often allowed to step into their husbands’ roles, participating directly in critical discussions. What she wore thus signaled not only her status, but also her authority to govern a household, manage employees, and, in this case, take part in war strategy. | ||

Garment - Style | Often layered, a kirtle was worn beneath this fitted gown. Made from finely woven wool or even silk, it was often dyed in the coveted Burgundian black. The collar was typically trimmed with fur, the type regulated by sumptuary laws. Due to the gown’s length, women would often lift it while walking, though the hem still tended to sweep the ground and collect dirt. A long train signaled high status and was rarely an issue unless one had to work. With tight-fitted, canonical sleeves, these gowns were never intended for labor or for spending long periods outdoors. | ||

Headdress | This pointed headdress is called a hennin, once worn by noblewomen in the 15th century. Stiffened with wire and canvas, this one reaches nearly 20 inches tall, a towering symbol of status and elegance. Sumptuary laws even dictated how tall a hennin could be, with noblewomen allowed up to three feet. Some doorways had to be raised so women could enter a room without bending or removing their headdresses, which were deemed impractical for daily laborers. | ||

War Stuffs | Medieval warfare wasn’t just brute force. It was choreography in real time using instruments, banners, and signals that guided troops cutting through the chaos to deliver commands mid-battle. |

Environment Models: Leartes Studios, Quixel

All sources can be found in linked paper!

Comments